Global Information Hub on Integrated Medicine.2016.pg 1-28.

Meor Hakimi Meor Idris , Ida Farah Ahmad , Mohd Khairuddin Che Ibrahim, Siti Nurulsyuhada Rosli, Nurul Nadhirah Abdul Razak, Farhanah Ramawi, Nur Hazwani Norhata, Ami Fazlin Syed Mohamed

Information Unit, Herbal Medicine Research Centre, Institute for Medical Research, Jalan Pahang, 50588 Kuala Lumpur

ABSTRACT

Background. Insomnia is a type of sleep disorder that affects the quality of life of many people worldwide. It is presented as primary disorder or secondary to other underlying diseases. Music therapy has been used as a treatment option for insomnia. This review was conducted to assess the evidence of music therapy effect on insomnia among adult population. Method. A search was made on randomised controlled trial (RCT) articles published in English language from year 2000 onwards, using a combination of selected search terms from eleven electronic databases; PubMed, SpringerLink, LILACS, Scopus, EBSCOhost, ScienceDirect, Cochrane library, Thieme, Nature, OvidSP and Wiley. Researchers were divided into two groups (four people in each group) to determine eligibility of the selected articles. The articles were selected based on the predetermined criteria that are; study samples, type of intervention, comparison, outcomes and study model (SICOM). Studies included in this review were then critically appraised, and risks of bias were assessed using the Cochrane criteria. Result. A total of 144 abstracts were identified, reviewed and extracted. The final number of articles included is seven RCTs that met the SICOM criteria. Only one study was associated with an overall low risk of bias. Music therapy given at various durations and frequencies showed significant (p < 0.05) improvement of sleep quality and sleep quantity in all studies. It also showed positive effect on psychological and physiological parameter of participants in four studies. However, there was no significant correlation found between those parameters to sleep quality and quantity. Conclusion. There was inadequate evidence to conclude the effect of music therapy on insomnia. Future studies should recruit enough sample sizes to enhance the strength of the outcome.

Keywords

Randomised controlled trial; music therapy; insomnia; sleep quality; sleep quantity

INTRODUCTION

Insomnia is one of the common sleep disorders affecting people from all walks of life. There are several classifications and definitions which can be used to describe insomnia. In general, insomnia can be classified as a primary disorder, a secondary disorder or exists as comorbidity to other diseases [1]. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-2) describes insomnia as a complaint of symptoms varying from difficulty in initiating sleep, difficulty in maintaining sleep, waking up too early, chronically non-restorative sleep or poor quality of sleep which will lead to daytime dysfunction [2]. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM IV-TR) categorised insomnia into primary insomnia, and insomnia related to other causes, including major depressive and anxiety disorders. (AM J Psychiatry, 2008) Both the ICSD-2 and DSM IV-TR described the duration of symptoms to last for at least 1 month period [3]. On the other hand, the Classification of Mental and Behavioral Disorders (ICD-10) described and classified insomnia according to the underlying pathology as nonorganic insomnia and nonorganic disorders of sleep wake schedule [4].

A study in the United States of America saw the prevalence of insomnia ranging from 6 – 18% depending on the definitions used in diagnosing the illness [5]. In the European population the prevalence of insomnia range from 6 – 22% [6] and a cross-sectional survey involving 70115 respondents in Finland from 1979 – 2002 noted an overall prevalence of insomnia at 18-19% [7]. In Asian population, the prevalence is much higher at 25% in Taiwan [8] and 39.4% in Hong Kong [9]. In Malaysia, a study conducted in year 2004 noted a prevalence of insomnia symptoms among adults at 33.8% while 12.2% were diagnosed with chronic insomnia [10]. Higher prevalence rate were also observed in women compared to men [5,6,8,9,11] and it is more common in the elderly [5,8,12]. Patients suffering from this sleep disorder usually complain of excessive sleepiness in daytime, inability to concentrate, exhaustion, poor memory and feeling depressed [10]. These consequences will lead to negative impact on work performances [13] and daily activities [12,14].

Nowadays, there are several treatment approaches available to combat this health problem. These include pharmacological treatment such as medications prescribed by health care practitioners, over-the-counter medications [15,17] , non-pharmacological treatment such as cognitive-behavioural treatment and sleep hygiene as well as herbal or natural remedies [17,21]. The most commonly prescribed medications by health care practitioners are benzodiazepines, non-benzodiazepines, melatonin-receptor agonist and antihistamines [16]. Even though these medications have shown promising efficacy, they do carry multiple adverse effects such as headache, dizziness, somnolence, fatigue and nausea [22,23].

Several meta-analyses and studies carried out indicated that sleep deprivation impairs human cognitive and motor functions (Pulcher & Huffcutt, 1996; Aigboje, 2014), and contributes to negatively impacting reaction time, accuracy and speed (Griffith, 2006) Due to the emergence and development of complementary medicine, most patients and health care practitioners are looking into this type of intervention hoping for at least equivalent efficacy but with less adverse and unwanted effects compared to the pharmacological intervention. One of the interventions available is music therapy. This therapy may include usage of a wide range of music tempo and rhythm, from classical music to new-age music. Music is being used as a sole-treatment or as a complement to other interventions in certain health conditions. Music therapy has been studied and used in multiple physical and mental health conditions such as in pain management [24,26], psychiatric illnesses such as depression and anxiety [27], Alzheimer’s disease [28] and as a therapeutic tool for children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder [29].

How about insomnia? Can music therapy be used and has beneficial effect on insomnia? Are there any adverse effects from this intervention? Up to date, there are many studies on music therapy and insomnia carried out by researchers all around the world. A systematic review approach will provide a better and more concise conclusion regarding the above matter. Therefore, the objective of this study is to review the effect of music therapy on insomnia.

METHODS

Search strategy and study selection

- Language of studies: Only articles in English language are included as there is language proficiency limitation for others.

- Electronic searches: A literature search was performed in the following electronic databases and trial registers from the commencement of the search activity to September 2013: PubMed, SpringerLink, LILACS, Scopus, EBSCOhost, ScienceDirect, The Cochrane Library, Thieme, Nature, OvidSP, Wiley.

- Searching other resources: If the full text of the articles could not be retrieved from the enlisted databases, the researchers requested the assistance of the Institute of Medical Research library to procure the full text articles.

- Search terms: The following combinations of search terms were used: Sleep AND Insomnia, and Music AND Insomnia. The reference lists within the original and review articles were also reviewed to identify additional relevant studies.

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Studies inclusion in the review was based on the following criteria:

- Types of study sample: This review included studies on adult patients (18 years old and above) diagnosed with insomnia (primary insomnia) and patients with sleep disturbances secondary to other diseases or other pre-identified factors (secondary insomnia). There were no restrictions as to gender, ethnicity, locality or types of setting.

- Types of intervention: This review included all studies using any genre of music as their intervention.

- Types of comparison: The comparison group included (a) group without music intervention (b) group with intervention other than music.

- Types of outcomes:

- Primary outcomes: The primary outcomes were evaluated based on the sleep quality and sleep quantity. The measurement tools applied for sleep quality in these studies were Pittsburg sleep quality index (PSQI), modified Verran and Synder-Halpern (VSH) sleeping scale, morning questionnaire and polysomnography. The measurement tools for sleep quantity are polysomnography and quantity of sleeping questionnaire.

- Secondary outcomes: Secondary outcomes and their measurement tools in this review include depression level using geriatric depression scale (GDS), Montgomery Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS) and Beck depression inventory (BDI). The anxiety level was measured using state trait anxiety inventory (STAI) while fatigability measured using fatigue scale (FS). Physiological parametres measured include systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and heart rate (HR).

- Types of study model: All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were eligible for inclusion.

Study selection

Eight researchers were divided into two groups (four people in each group). These two groups conducted the articles search separately to match the inclusion criteria using all the databases mentioned. At the end of the search, both groups sat together to identify their duplicated articles and number of articles matched the inclusion criteria were recorded. All of the selected articles were then reviewed critically by all researchers. Articles which are finally included in this study were carefully selected guided by adherence to all inclusion criteria, critically appraised and disagreements were resolved by consensus.

Risk of bias assessment

Each category was judged by using the Cochrane ‘Risk of bias’ tool [30]. There are six criteria to appraise all the included studies which are random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other bias. Each criterion was rated as low, high or unclear risk.

RESULTS

Search results and study designs

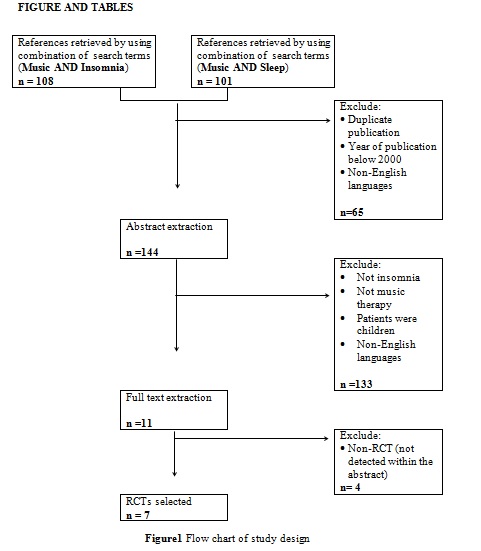

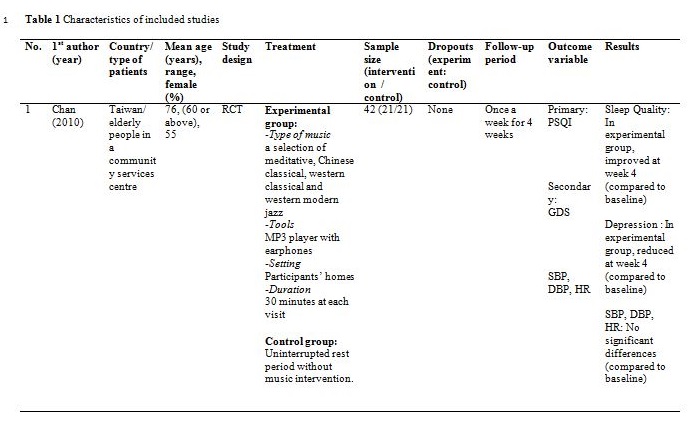

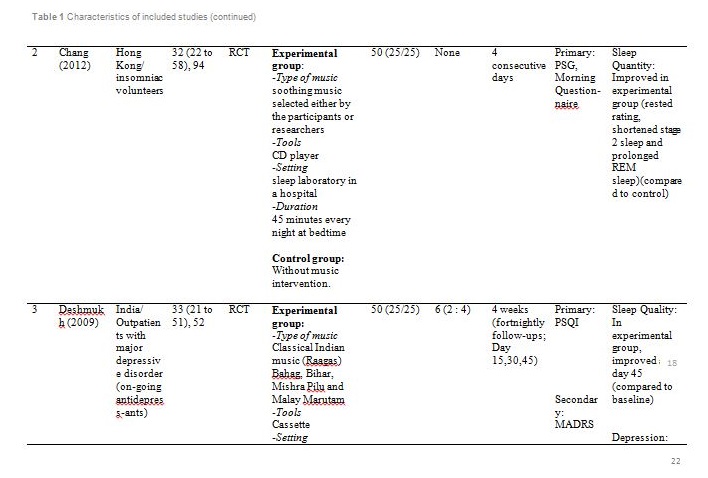

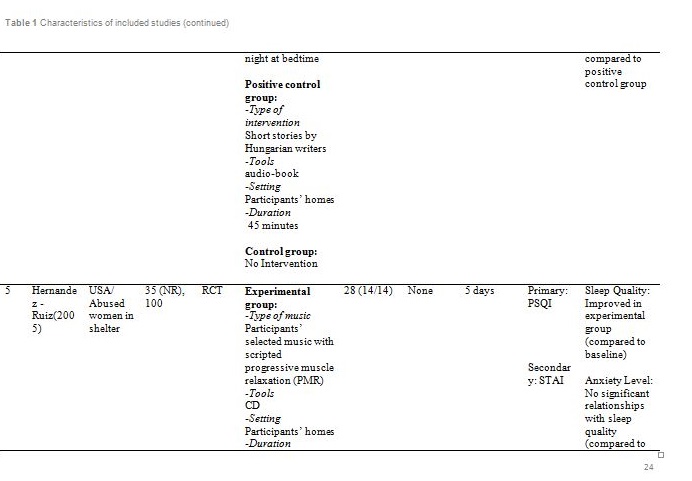

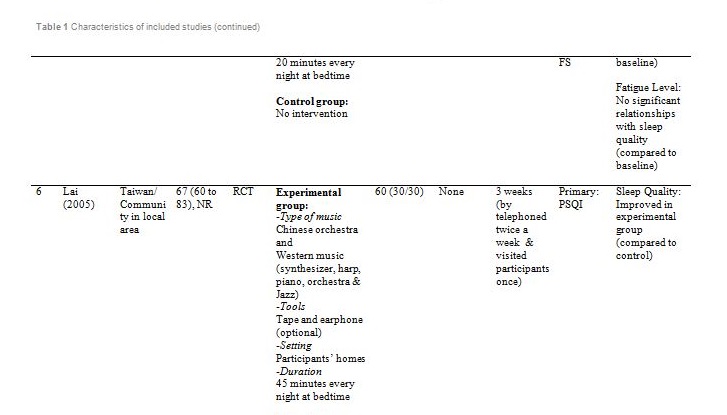

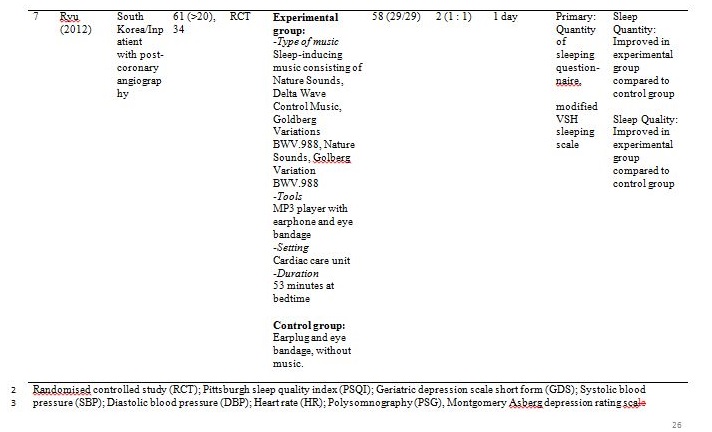

Figure 1 summarised the study design for selection of the included articles. Initially, a total of 209 potential titles from the keywords of Music AND Insomnia; and Music AND Sleep were screened from all electronic databases for eligibility. 144 abstracts were chosen for assessment, of which 11 articles met the inclusion criteria. However, only seven articles are randomised control trials (RCTs). Table 1 showed detail information of the included articles with respect to the study sample, intervention, comparison, outcomes and study model.

Participants

The studies were carried out in Taiwan [31,32], Hong Kong [33] ,India [34], Hungary [35], South Korea [36] and the United States of America [37]. Sample sizes varied from 28 to 94, with a total of 382 participants aged from 19 and above. Out of seven, only one study reported patients with primary insomnia [33]. The other six studies characterised their participants as having secondary insomnia comprising of volunteers from community services center [31], selected local areas [32], shelter for abused women [37], a university [35], outpatients with major depressive disorder [34] and inpatients with post-coronary angiography [36].

Outcome measures employed

Five studies employed a self-rated Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI) questionnaire to assess sleep quality and disturbances over seven components: sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication and daytime dysfunction [31,32,34,35,37]. A score of greater than five is indicative of poor sleep quality.

Other measurement tools used for evaluation of sleeping quality and quantity were Polysomnography (PSG)[33], morning questionnaire [33], modified VSH sleeping scale [36] and quantity of sleeping questionnaire [36]. The PSG measured total sleep time, sleep efficiency, sleep onset latency, wake time after sleep onset, number of awakenings, percentage of time in stages 1,2,3,4, and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and arousal index (number of electroencephalographic arousals per hour of sleep). The morning questionnaire recorded patient’s bedtime, total sleep time, time taken to fall asleep, number of awakening, time spent awake during the night, wake up time and a subjective evaluation of feeling rested. The modified VSH sleeping scale measured characteristics of sleep inducing frequency of awakening while sleeping, depth of sleep and self-evaluation of sleep. This eight-question measurement tool has a scale score range from 0 to 80 points (the higher score, the better sleep quality). Quantity of sleeping questionnaire records the total duration of sleep in minutes or hours.

For assessment of the secondary outcome, Deshmukh used a 6-scale Montgomery Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS) to measure depression level [34]. In a study by Harmat, depression was measured using Beck depression inventory (BDI)[35]. BDI is a 9-item questionnaire with score greater than 26 is an indicative of high depression. Chan and Lai used a 15-item geriatric depression scale (GDS) questionnaire to assess depression as a score of greater than six is indicative of being depressed [31,32]. Chan also measured physiological parameters including level of systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure and heart rate [31]. Other studies used a 20-item State-trait anxiety inventory (STAI) to assess anxiety level [33,37], and a fatigue scale with 18-item scale (0 to 10) to assess fatigue and energy level at waking time [37].

Intervention type

Basically all the studies used predetermined music or songs in their interventions. All participants were supplied with CDs [33,35,37], an MP3 player [31,36] or a cassette tape [32,34]. The control groups were without any tools or intervention and allowed to have uninterrupted rest. However, for studies by Deshmukh, the control group received hypnotic medications (Diazepam and Chlordiaxepoxide) [34] and Ryu’s were provided with earplug and eye bandage [36]. All experiments were set at the participants own homes, except for Chang which was carried out in a sleep laboratory [33], while Ryu in a cardiac care unit [36]. The types of music offered to the participants varied between the studies. The music were generally soothing and provided comfort to the participants, such as meditative or Chinese and western classical or orchestral music [31,32]. Harmat applied classical music from Baroque to romantic on the participants and the positive control group were provided with Hungarian short stories on an audiobook [35]. Deshmukh used classical Indian music (Raagas) Bahag, Bihar, Mishra Pilu and Malay Marutam [34], whilst Ryu applied a sleep-inducing music involving nature sounds [36]. Chang had given a choice of soothing music or the participants own choice of songs [33]. Hernandez-Ruiz let the participants specify their own selection of artists and type of music/songs or supplied a collection of songs to those who did not specify their preference. Hernandez-Ruiz also accompanied the intervention with a scripted progressive muscle relaxation session [37].

These studies employed a variety of duration for the music intervention, as well as the frequency and interval between applications. Music duration is at 45 minutes in Chang [33], Deshmukh [34], Harmat [35] and Lai [32], whereas Chan [31], Hernandez-Ruiz [37] and Ryu [36] had the music full duration at 30, 20 and 53 minutes respectively, or let the music on until they fall asleep. Chan played the music during visits to the participants’ homes once a week for four weeks [31]. The rest of the studies had the participants play the music at bedtime every day [32,35,37] except for Ryu which study was only carried out on a one-time application of the music therapy [36]. However, the number of days and intervals of application also differ between studies. Chang’s was applied for four consecutive days [33], Hernandez-Ruiz for 5 days [37], Lai and Harmat for three weeks [32,35], and Deshmukh for four weeks [34]. Follow-up of the participants were carried out daily by Chang and Hernandez-Ruiz [33,37]. Chan and Harmat had the follow-up once a week [31,35], Deshmukh fortnightly (four follow-up consisted of day-1, day-15, day-30 and day-45) [34] and Lai twice a week [32].

Primary outcome measure: sleep quality and sleep quantity

The primary outcomes for the seven studies are sleep quality and sleep quantity. However, the outcome measurement scales varied including PSQI, polysomnography, morning questionnaire and modified VSH sleeping scale. Five studies measured the sleep quality using PSQI [31,32,34,35,37]. Improvement of sleep quality is determined by reduction of PSQI score compared to the baseline score or in comparison with scores from other groups. Even though these five studies used the same scoring parameters, the measurement was done at different points of time making it inequitable and impossible to compare among them.

Deshmukh showed at day 45, sleep quality in experimental group was improved with significant (p = 0.016) reduction of PSQI score compared to the control group (hypnotic medication) [34]. Lai showed at week 1, 2 and 3, sleep quality in experimental group was improved (p<0.01) compared to control (no intervention) [32]. Harmat observed a significant (p < 0.0001) improvement of sleep quality in experimental group compared to baseline. The sleep quality also significantly (p < 0.05) improved compared to the positive control (audiobook) [35]. The study by Chan showed at the fourth week of experiment, sleep quality in experimental group was significantly (p < 0.001) improved compared to the baseline [31]. Hernandez-Ruiz showed on the fifth day, sleep quality in experimental group was improved (p = 0.007) compared to the baseline [37].

Two studies measured both sleep quality and quantity as the primary outcomes. Chang measured sleep quality using PSG and morning questionnaire while sleep quantity was measured using PSG. There were 10 PSG parametres observed for sleep quantity in this study [33]. However, the only significant results were shortened stage 2 sleep (p = 0.03) and prolonged REM (p = 0.04) compared to control (no intervention). The morning questionnaire recorded higher rested rating score in experimental group proving sleep quality was significantly (p = 0.01) improved compared to control (no intervention).

Ryu measured sleep quality using modified VSH sleeping scale and sleep quantity using quantity of sleeping questionnaire [36]. Sleep quality was significantly (p < 0.001) improved and sleep quantity was significantly (p = 0.002) increased compared to control (earplug and eye bandage).

Secondary outcome measure

Apart from the primary outcome, the psychological and physiological parametres of the participants were also measured as these variables might affect sleep quality and quantity. Several tools were used to measure the level of depression including GDS, MADRS and BDI. Based on GDS; Chan stated the participants gained a normal score at week 4 [31]. Based on MADRS, scores at all follow-up visits showed a reduction from baseline but no significant difference was observed between the experimental and control group at all visits [34]. Meanwhile, comparing the pre-test and post-test BDI scores, the depressive symptoms decreased in the music group but not in the audiobook group [35]. Initial evaluation of participants showed mild to normal depressive symptoms [31,35]. Therefore, absence of significant correlation between depression and sleep patterns in all participants is acceptable.

Other psychological outcomes reported were the anxiety and fatigue level. According to Hernandez-Ruiz, those outcomes were described as dependent variables to the intervention. STAI measured the anxiety trait before and after music stimulation, while level of fatigue was measured at waking time [37]. This study showed that the music therapy was able to reduce the anxiety level. However, the pre-test and post-test results showed no significant relationships between anxiety levels and sleep quality as well as fatigue level and sleep quality. .

Chan analysed physiological parameters (SBP, DBP and HR) of each participant before and after music intervention [31]. However, no statistically significant differences were found for any of the parameter between the experimental and control group.

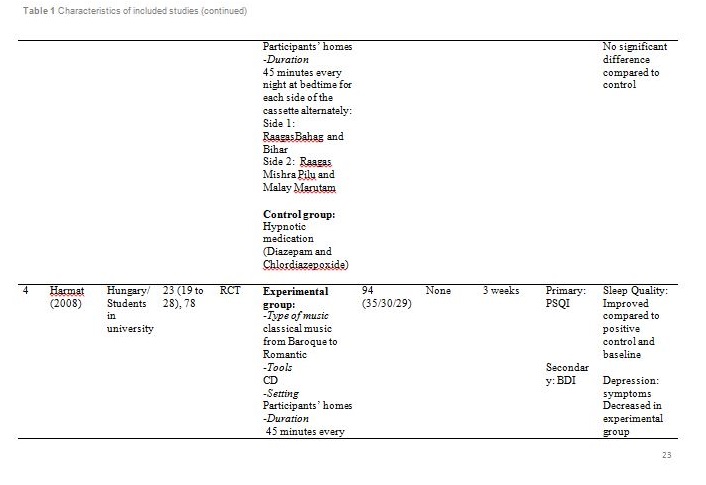

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias and quality of each RCT article were assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tooland summarised in Table 2.

- Two studies were identified to carry high risk of random sequence generation bias [34, 37]. Randomisation was not clearly mentioned in the study by Deshmukh [34]. In the study by Hernandez-Ruiz, participants were allocated into two groups after initial interview session with the researchers hence increasing the bias in randomisation process [37].

- Only two studies carried low risk of allocation concealment bias due to blinding of researchers [32,33].

- In terms of blinding of participants and personnel, all seven studies carried low risk of bias [31,37]. All participants knew they were in either experimental group or control group, and the investigators were not blinded too. However, this lack of blinding is not likely to influence the outcome.

- Four studies carried high risk of detection bias due to the unsatisfactory blinding of outcome assessment [3,31,32,35].

- High risk of attrition bias was noted in one study due to missing data have been imputed using inappropriate method (data of dropout participants were carried forward)[34].

- Selective reporting was found in two studies. In the study by Deshmukh, six participants dropped out from the study without any reason mentioned [34]. High risk of reporting bias noted in the study by Lai due to the absence of secondary outcome results [32].

- Other biases were observed in one study as insufficient sample size was used (only 21 samples used in each group, instead of 159 samples needed to detect a difference between group) and the study samples were not representing subjects with depression (the baseline score of geriatric depression scale for all participants were within normal range) [31].

FIGURE AND TABLES

Randomised controlled study (RCT); Pittsburgh sleep quality index (PSQI); Geriatric depression scale short form (GDS); Systolic blood pressure (SBP); Diastolic blood pressure (DBP); Heart rate (HR); Polysomnography (PSG), Montgomery Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS); Beck depression inventory (BDI); State trait anxiety inventory (STAI); Fatigue scale (FS); Verran and Synder-Halpern sleeping scale (VSH); Rapid eye movement (REM); Not reported (NR)

Table 2 Assessment of risk of bias

| Bias | Chan (2010) | Chang (2012) | Deshmukh (2009) | Harmat (2008) | Hernandez-Ruiz (2005) | Lai (2005) | Ryu (2012) |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | + | + | ? | + | – | + | + |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | – | + | – | – | – | + | – |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) | – | + | + | – | – | – | + |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) | + | + | – | + | + | + | + |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | + | + | – | + | + | – | + |

Other bias | – | + | + | + | + | + | + |

+ = low risk of bias; ? = unclear risk; – = high risk of bias

DISCUSSION

This review showed the effectiveness of music therapy on sleep quality and quantity in varied range of insomniac participants including volunteers from community services center, university students, abused women in shelter and inpatients with post-coronary angiography. The primary outcomes were similar in all studies although the participants came from different countries namely Taiwan, Hong Kong, India, Hungary, South Korea and the United States of America. Hence, music therapy can be accepted as an alternative treatment for insomniac patients across the culture, although they listen to different genres of soothing music.

Previous studies have reported that soothing music can be used to complement treatments of dementia and Alzheimer’s as well as to relieve labor pain [38]. In this review, soothing music has a relaxation effect which improved sleep quality and quantity in insomniac participants [39]. Six studies were carried out in controlled settings (participants’ home and sleep laboratory) to offer conducive sleep environment.

The possible underlying mechanism of music therapy on insomnia was not fully understood. Music therapy was believed to regulate the level of serotonin, norepinephrine and adrenalin and activates the release of the so-called “feel good” hormone (dopamine) [40]. This promotes relaxation and sleep.

There are a few limitations in this review. A fair comparison and analysis could not be carried out on the seven selected RCTs due to dissimilarity of methods applied by these studies. There was no standardised method used in terms of music duration, frequency and intervals between therapy applications. There were two types of outcome measurement tools (objective: PSG, subjective: PSQI, and modified VSH sleeping scale) used in the studies. Among the subjective measurement tools (questionnaires), different parameters and scoring systems were used making it impossible to equitably compare these studies. Due to only a single study on primary insomnia found, the effect of music therapy on specific type of insomnia (primary or secondary) could not be determined. Six studies were observed to have high risk of bias which demands for a more cautious interpretation of their results.

CONCLUSION

From this review, the seven studies showed that listening to music may promote quality sleep in insomniac adults. Music contributed to positive effects on physiological and psychological parameters of the insomniac patients. However, there was no significant correlation between those parameters to sleep quality and quantity probably due to small sample sizes used. Thus, future studies should recruit enough participants to enhance strength of the outcome. This will add value in establishing music therapy as one of the treatment options for insomnia. This intervention is practical as it is easy, cheap and safe to apply.

REFERENCES

- Harvey AG. Insomnia: Symptom or diagnosis? Clin Psychol Rev. 2001;21(7):1037-59.

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The international classification of sleep disorder, revised: diagnostic and coding manual (ICSD-2). Second ed. Chicago, Illinois: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV-TR), text revision. Fourth ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

- Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6(2):97-111.

- Hajak G. Epidemiology of severe insomnia and its consequences in Germany. Eur Arch Psy Clin N. 2001;251(2):49-56.

- Talala KM, Martelin TP, Haukkala AH, Härkänen TT, Prättälä RS. Socio-economic differences in self-reported insomnia and stress in Finland from 1979 to 2002: a population-based repeated cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:650-.

- Kao C-C, Huang C-J, Wang M-Y, Tsai P-S. Insomnia: prevalence and its impact on excessive daytime sleepiness and psychological well-being in the adult Taiwanese population. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(8):1073-80.

- Wong WS, Fielding R. Prevalence of insomnia among Chinese adults in Hong Kong: a population-based study. J Sleep Res. 2011;20(1 Pt 1):117-26.

- Zailinawati A, Ariff K, Nurjahan M, Teng C. Epidemiology of insomnia in Malaysian adults: a community-based survey in 4 urban areas. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2008;20(3):224-33.

- López-Torres Hidalgo J, Navarro Bravo B, Párraga Martínez I, Andrés Pretel F, Téllez Lapeira J, Boix Gras C. Understanding insomnia in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psych. 2012;27(10):1086-93.

- Zailinawati AH, Mazza D, Teng CL. Prevalence of insomnia and its impact on daily function amongst Malaysian primary care patients. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2012;11(1):9.

- Kucharczyk ER, Morgan K, Hall AP. The occupational impact of sleep quality and insomnia symptoms. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(6):547-59.

- Léger D, Partinen M, Hirshkowitz M, Chokroverty S, Touchette E, Hedner J. Daytime consequences of insomnia symptoms among outpatients in primary care practice: EQUINOX international survey. Sleep med. 2010;11(10):999-1009.

- Richey SM, Krystal AD. Pharmacological advances in the treatment of insomnia. Curr Pharm Des. 2011;17(15):1471-5.

- Schutte-Rodin S, Broch L, Buysse D, Dorsey C, Sateia M. Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4(5):487-504.

- Pigeon WR. Diagnosis, prevalence, pathways, consequences & treatment of insomnia. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:321-32.

- Siebern AT, Suh S, Nowakowski S. Non-pharmacological treatment of insomnia. Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9(4):717-27.

- Poluektov MG. Origin and treatment of insomnia: current status of knowledge. Ross Fiziol Zh Im I M Sechenova. 2012;98(10):1188-99.

- Morin CM, Bootzin RR, Buysse DJ, Edinger JD, Espie CA, Lichstein KL. Psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia:update of the recent evidence (1998-2004). Sleep. 2006;29(11):1398-414.

- Williams J, Roth A, Vatthauer K, McCrae CS. Cognitive behavioral treatment of insomnia. Chest. 2013;143(2):554-65.

- Anne M, Holbrook RC, Ann L, Chiachen C, Derek K. Meta-analysis of benzodiazepine use in the treatment of insomnia. Can Med Assoc J. 2000;162(2):225-33.

- Buscemi N, Vandermeer B, Friesen C, Bialy L, Tubman M, Ospina M, et al. The efficacy and safety of drug treatments for chronic insomnia in adults: a meta-analysis of RCTs. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(9):1335-50.

- Korczak D, Wastian M, Schneider M. Music therapy in palliative setting. GMS Health Technol Assess. 2013;9:Doc07.

- Archie P, Bruera E, Cohen L. Music-based interventions in palliative cancer care: a review of quantitative studies and neurobiological literature. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(9):2609-24.

- Korhan EA, Uyar M, Eyigor C, Hakverdioglu Yont G, Celik S, Khorshid L. The effects of music therapy on pain in patients with neuropathic pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2013.

- Heise S, Steinberg H, Himmerich H. The discussion about the application and impact of music on depressive diseases throughout history and at present. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2013;81(8):426-36.

- Delphin-Combe F, Rouch I, Martin-Gaujard G, Relland S, Krolak-Salmon P. Effect of a non-pharmacological intervention, Voix d’Or, on behavior disturbances in Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. Geriatr Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieil. 2013;11(3):323-30.

- Brown LS, Jellison JA. Music research with children and youth with disabilities and typically developing peers: a systematic review. J Music Ther. 2012;49(3):335-64.

- Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 2011. The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from: www.cochrane-handbook.org.

- Chan MF, Chan EA, Mok E. Effects of music on depression and sleep quality in elderly people: a randomised controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2010;18(3-4):150-9.

- Lai H-L, Good M. Music improves sleep quality in older adults. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53(1):134-44.

- Chang ET, Lai HL, Chen PW, Hsieh YM, Lee LH. The effects of music on the sleep quality of adults with chronic insomnia using evidence from polysomnographic and self-reported analysis: a randomised control trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(8):921-30.

- Deshmukh AD, Sarvaiya AA, Seethalakshmi R, Nayak AS. Effect of Indian classical music on quality of sleep in depressed patients: a randomised controlled trial. Nord J Music Ther. 2009;18(1):70-8.

- Harmat L, Takács J, Bódizs R. Music improves sleep quality in students. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(3):327-35.

- Ryu M-J, Park JS, Park H. Effect of sleep-inducing music on sleep in persons with percutaneous transluminal coronary angiography in the cardiac care unit. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(5-6):728-35.

- Hernández-Ruiz E. Effect of music therapy on the anxiety levels and sleep patterns of abused women in shelters. J Music Ther. 2005;42(2):140-58.

- Phumdoung S, Good M. Music reduces sensation and distress of labor pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2003;4(2):54-61.

- Gimeno MM. The effect of music and imagery to induce relaxation and reduce nausea and emesis in patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy treatment. Music Med. 2010;2(3):174-81.

- Chanda ML, Levitin DJ. The neurochemistry of music. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17(4):179-93.